The Artist's Talk: Exploring Remote Location Ghost Schools and Voices from the Past

A Literal and Metaphorical Journey

Schoolhouse Odyssey photographer and exhibition curator Diana Schoenfeld will present an illustrated “artist’s talk” describing her twenty year documentation of 180 little known American schoolhouses and preservation of related oral histories. Slides of the original black-and-white photographs will accompany the talk.

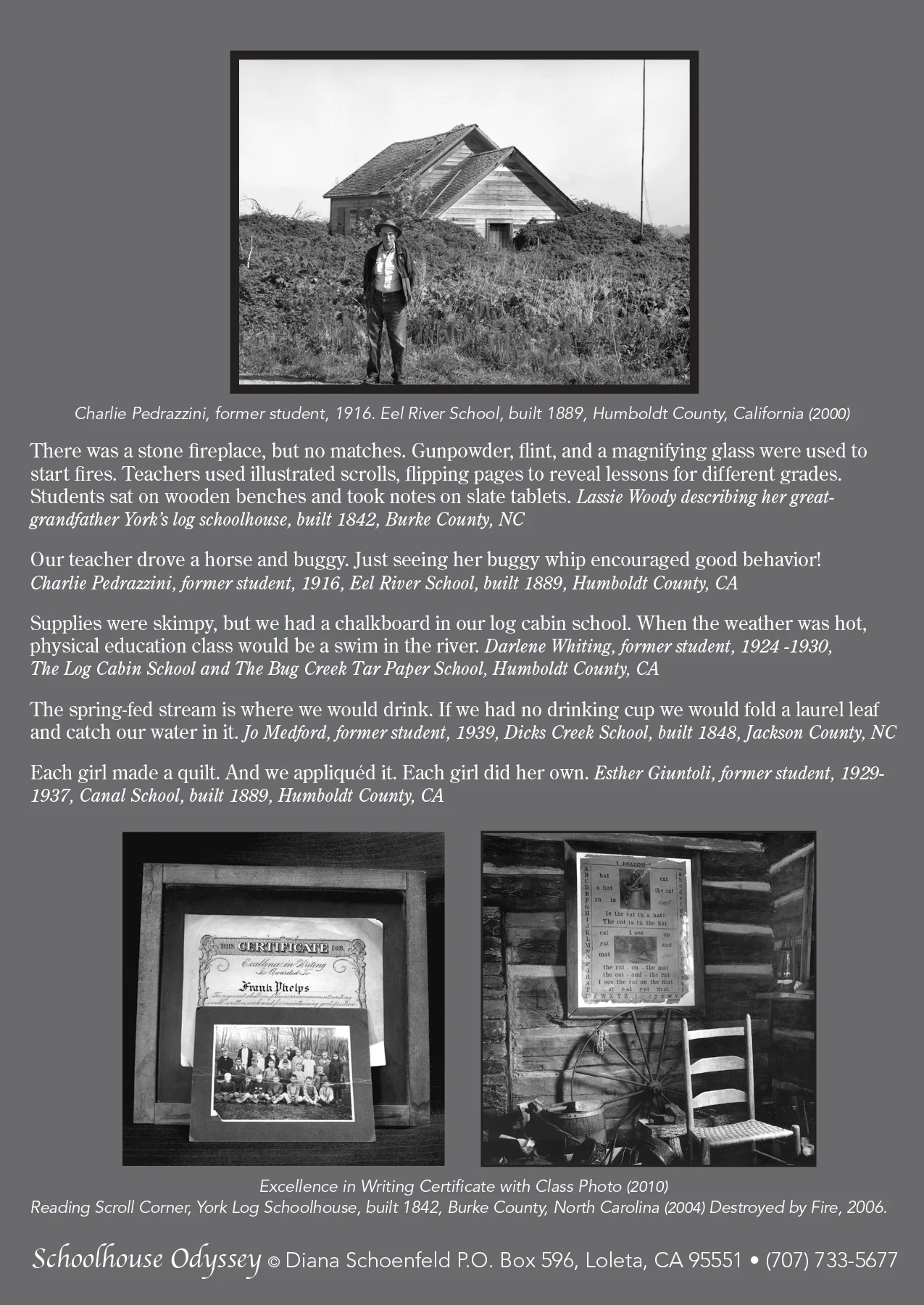

Schoolhouse Odyssey is an exhibition of 90 gelatin silver photographs accompanied by 19th century schoolbooks and related ephemera, transcribed memoirs, and literature, both antique and contemporary. The slide presentation includes individual images and views of the exhibition with commentary by the photographer. Exhibition prints, sample memoirs, and audio of voices from the past will be available. School buildings are shown in their landscape settings with antique playgrounds occasionally present. The buildings date from 1794 to the 1930s. Rosenwald schools and abandoned W.P.A. schoolhouses have been found. Some interiors are preserved, while others are in states of abandonment and ruin, their schoolroom remnants succumbing to exposure, encroaching plant and animal life, and human debris. Geographic locations range from Vermont to California, from the Deep South to the Pacific Northwest. Tiny architectural gems are among the quaint, the faded, the humble old schools, but a melancholy beauty pervades them all.

Cross Rock Schoolhouse, built 1900, Buncombe County, North Carolina

“Today, many schoolhouses are forgotten, camouflaged by overgrowth, deteriorating and seldom noticed... others are still used as community centers, tobacco barns, museums and even residences. They are constructed of logs, wood, sod, brick, and stone, and in the West, adobe, but all give testimony to their past as both receptacles and symbols of learning. . . . As documents, these photographs inform us, but as poetry they enchant and elevate our souls.” (From exhibition essay by Darwin Marable)

Background

This work was undertaken in the spirit of curiosity and adventure and remains so to this day. I quickly learned that people were eager to help me find my way --

including into their personal life stories where reside decades of memory of vanished schoolhouses. One tells of a settler’s log cabin which became Bug Creek School. It functioned as an “emergency school” in the coastal hills of northern California. The role this rustic schoolroom played in homesteaders’ lives left indelible memories. One student in a 1924 class of “five and a fraction” described schooldays intertwined with the surrounding natural world and physical difficulties of that era. Her descriptions of horseback riding in view of mountain lions, of weeks of impassible snow or flooding creeks, of invented games and learning from native children, are vestiges of life in what remains a sparsely settled landscape.

A primary source of this study lies in my own memories of a landscape called the Deep South. I knew it before the bulldozers and tractor blades of aggressive development destroyed so much physical evidence of the past. In the 1950s and 1960s, the countryside of Georgia, Florida, and the Carolinas was rich with picturesque buildings representing layers of partially forgotten history. I was fascinated by the co-mingling of architecture with the natural world. During the hot, humid summers, plants like kudzu, honeysuckle, and poison ivy would overtake acres of landscape. Isolated old buildings were engulfed in this lush growth. This particular American environment permeated my imagination until 1973 when I left Georgia for New Mexico, finding there a land arrayed in timeless adobe buildings - a sculptural architecture defined by intense sunlight and shadow.

I began photographing one-room schoolhouses while traveling to teach in different parts of the country. Twenty years later, I continue to explore the ghost school subject, recently returning to do so in New Mexico. There, one remote schoolhouse, built in 1890, is still graced with its tall wooden bell tower. It stands in proud abandonment, isolated in the expansive fields of that state’s southwestern hills. Elsewhere, two others are constructed of terrone - a sod brick cut from the river-bottom of the Rio Grande. Farther north, a narrow, pitted, rock-strewn road leads precariously uphill to the ghost town of Silver City, Idaho. The treacherous drive is worth it, for there stands a stunning 1892 schoolhouse, white walls radiant in brilliant sunlight.

The visual and literary results of my journeys are presented with objects related to schooldays of the past. Memoirs of people whose lives were touched by these little schools are placed on pedestals in front of the photographs. They are intended to be picked up, handled, and read, as were the old schoolbooks on view in display cases. Years passed before I realized that on a deeper level, my personal Schoolhouse Odyssey is more than a pictorial study of old schoolhouses. It is a search for, and a way to recover, a lost landscape of home, represented by these little buildings wherever they yet stand.

One Viewer’s Response

“What I could not anticipate was the . . . soul journey from connecting to the photographs, writings, and objects across time and place, evoking memory and imagination . . . . The relationship of objects to one another, the arrangement of photographs like pages in a book, the writings interspersed with consideration like chapter breaks, the housing of objects precious and preserved, and the interactive elements inviting participation, all touchstones to the past, as well as profound reminders of what is so relevant now. In overheard conversations, there were the discoveries of common experience or shared story . . . the threads that link us all. . . .

It was the transcendent quality of Schoolhouse Odyssey that served not only to inform and inspire, but also to satisfy longing. The longing for what I know as vertical (or depth) experience is the satisfaction from this exhibition. Each visual connection and its relationship to the larger body of work, comes alive with symbolism and metaphor. Leaving the museum, I was savoring this personal experience and hoping others would have the same opportunity. "